Inferno by Dante, tr. Hollander

Purgatorio by Dante, tr. Hollander

Paradiso by Dante, tr. Hollander

The Aeneid by Virgil, tr. Mendelbaum

The New Science by Giambattista Vico

Mimesis and Dante: Poet of a Secular World by Auerbach

DANTE IN SEZZE

First I read the Commedia (1321), Dante’s three-part, 14,233-line, encyclopedic, divine poem, was in 2013. I was twenty-two. I read it quickly, reading minimal annotations—the Mendelbaum translation, during my final semester of college.

I got the basics: Dante has been banished and exiled, and so reads his favorite poet Virgil, who guides him out of the darkness he finds himself in; he writes a poem mirroring this process, imagining Virgil leading him through Hell and up the mountain of Purgatory; before eventually being led up to Paradise by a woman Beatrice.

If you asked me what the meaning of the poem was, I’d likely say something like,

When you find yourself exiled, castigated by your peers, in a crisis you see no way out of, go inward; find a literary father, read him diligently, let him lead you through your hell of unknowing; embark on the treacherous path of alchemizing your life into art, following the precepts of your chosen guide; and only then, once you’ve ventured through that darkness, climbed the mountain of Purgatory, can you let a lover lead you back into the world.

This is a perfectly reasonable reading. Dante can’t return to his home city of Florence, he’s been kicked out by his wife and wife’s family for political reasons, and so he relates to and retells Book VI of Virgil’s the Aeneid, in which Aeneas, after being ousted from his home city of Troy by the Greeks, in the Trojan war, descends into the underworld on his way to Rome.

Dante, went my twenty-two-year-old thinking, was just rigorously reading his favorite author, emulating his form, charting how he led him him out of a crisis, before being led by his lover Beatrice back into the world.

And this would prove relevant to what I was on then: I’d just spent that year reading and writing about Bolaño, my chosen guide, for my undergrad thesis, living with my girlfriend. And then would get exiled, when my thesis got rejected and I wasn’t able to graduate due to needing to complete a final credit and being unable, for financial reasons, to return.

And so, in 2014, on the heels of this maiden, somewhat surface reading of Dante, I did what my Virgil (Bolaño) said to do, which was, as I saw it, to start walking across the country, sleeping wherever I ended up each day, and only setting something down if it was worth setting down. And only once I’d done this, I thought, could I face up to my girlfriend, my Beatrice, and return to her and the world.

I’d go on to walk for 100 days—the same number of cantos in Dante—following the dictum first of my Virgil, Bolaño, of seeing what’s outside the window, writing in direct contact with the world, doing like Amalfitano, the geometry teacher in part two of 2666 who, while going mad, stays calm and solves the geometry problem no one else even understands by hanging the book outside on a clothesline, to let it get battered by the elements. Before, like Dante, after climbing the mountain of Purgatory (walking across Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and mind-numbingly flat Kansas), I’d do like Dante does at the top of the mountain of Purgatory, as he approaches the Garden of Eden, leave Virgil behind and start following Beatrice—let my girlfriend pick me up and start a life together in California.

(Although, perhaps notably, I actually stopped at the base of the mountains—the Rockies—so perhaps I only made it through Hell; in any case, this is what, for the past ten years, Dante has meant to me.)

I. Holy Week…

It wasn’t till this past spring, till right around the spring equinox of my thirty-third year, that I felt moved, indeed divinely called, to revisit Dante.

We were coming up on the three-year anniversary of a catastrophic Holy Week, during which three things happened in quick, shocking succession: the novel I’d been working on with my mentor and guide, Gian, the editor and publisher of Tyrant Books, for the previous eighteen months had finally, or so it seemed, been birthed into completion; my girlfriend Kyra, who I’d been with for the past eighteen months, had an adverse reaction to her medication and took her own life; and not 72 hours later, I spoke to Gian for the last time—he’d been in town, visiting from his home in Italy, to try to secure investors for the new press he wanted my book to spearhead—on Palm Sunday, I’d later realize. He would overdose that night. No one had heard from him, and we wouldn’t realize this till Holy Wednesday. And Kyra’s friends and family and I would bury Kyra that Friday—Good Friday.

Around this time, I was considering traveling back to Gian’s home in Sezze, Italy, like I’d done over Christmas of 2020, when Gian flew me out to do final edits on my book. We’d worked on it over a year; we’d done four rewrites. This was peak Covid, a month after the 2020 election, the travel restrictions were heavy. But it was a thing Gian was adamant on doing, editing in person. He was generating hype for the new press. This was months before he died.

Shortly after his death, Catherine, a writer and close friend of Gian’s, started a foundation, the Giancarlo DiTrapano Foundation for Literature and the Arts, to fly writers out like I did that Covid Christmas, to hold residencies like he used to hold, to keep his memory alive. She’d given me an open invitation to come out and stay on the property, in a mentorship capacity, during the residency.

Dante had been important to Gian, it was one of the books Gian compared my novel to, in handwriting (if jokingly, in that way where you can’t tell whether or not it’s a joke), on the back of the last version he edited. Like Dante, we were inventing a new language, a new type of vernacular.

But so I’d already been thinking about Holy Week, about the meaning of stories of death and rebirth, starting to understand the connections between Christ’s Good Friday descent and older, pagan underworld harrowings, reading Holy Week texts only, trying to make sense of the utterly nonsensical, when I came upon another discovery.

Dante’s Commedia is not just a retelling of Aeneas’s descent and resurrection; it also mirrors Christ’s—it starts on Good Friday and spans one week.

And Beatrice wasn’t just a symbol; she was a real woman, who died in 1290, at age 25, ten years before Inferno is set.

More, the day Dante harrows Hell, the day the Inferno is set, is Good Friday as it’s observed in the classic Christian calendar, March 25—the same day I signed Gian’s contract, the day Kyra died. “Dante could hardly have chosen a more propitious date for a beginning: March 25 was the anniversary of the creation of Adam, of the conception and of the crucifixion of Christ.” (Inf. I.1, notes)

This hits me like lightning.

I didn’t realize Dante was retelling the story of Holy Week, nor that Beatrice was a real woman, who lived and died, whose soul Dante is re-communing with.

It’s at this moment that I realize I must reread Dante and return to Sezze.

II. Dante thinks he’s a sacred scribe...

Dante is midway through his life—around the age Christ lived to—when he finds himself in a dark wood, the straight way lost. In a state “so bitter death is hardly more so.” (Inf. I.7)

He is, if not explicitly suicidal, feeling a type of crisis like he wouldn’t mind if he died.

The poem begins right before dawn on Maundy Thursday, the night Christ goes out and is betrayed, in the year 1300, and it remains Maundy Thursday through the second Canto, in which he encounters Virgil, the Roman poet from right before Christ (70–19 BC).

Right off the bat, Dante is “trying to remember” all he’s seen, telling the reader he’s doing his best to. Claiming that this all happened just like he’s about to tell it. Worried people will think him mad for telling of how he did. “I am not Aeneas, nor am I Paul” (II.32)—Aeneas meaning the hero of Virgil’s Aeneid who, after losing the battle of Troy, on his way to Italy to found Rome, washes up on the shore near Naples and descends into the underworld to speak to his father and his deceased lover Dido; and the apostle Paul who, in AD 55, twenty years after Christ’s death and resurrection and ascension, writes that he too ascended to heaven, “was caught up into Paradise and heard inexpressible words, which man is not permitted to speak.” (II Cor. 12:4)

Dante adds, “Neither I nor any think me fit for this… I fear it may be madness.” (Inf. II.33-35)

Dante, as a regular guy, is comparing himself to the cthonic heroes of yore, who ventured into the underworld and resurrected back to earth to tell about all they saw (Aeneas goes into Dis before he can found Rome; Odysseus, on Circe’s orders, in Book XI of The Odyssey, must harrow Hades before he can return home to Ithaca; and the myths of Hercules and Orpheus both involve journeys into the underworld).

Dante is also claiming he ascended to the heavens, meaning the literal heavens, from planet to planet, star to star, in order of ascending distance from earth according to the Ptolemaic system of his time (the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn—where Beatrice leads him, in Paradiso), till he sees the light that illuminates all the stars, “the Eternal light,” (XXXIII.124) that is to say God himself, at which point, overwhelmed by all he’s seen, his wings fail, his mind is struck by a bolt of lightning, (XXXIII.140-2) and he tumbles back down to earth.

The Commedia ends with him saying he must rely only on his will, desire, and Love—the Holy Spirit—to try to communicate all he’s seen.

He’s claiming, in other words, to have been granted a divine vision, to have the status of a sacred scribe, like the authors of the Bible—Paul, John—were inspired by God to write what they wrote about Christ.

And the timeline of his poem reflects this explicitly: once through his despair and confusion on Maundy Thursday, Dante enters Hell proper, descending, for the next twenty-four hours, deeper and deeper into the underworld, completing his descent in Judas’s circle, at the end of Good Friday. Just like Christ enters the underworld—is crucified and buried—on Good Friday in the year 34.1

He then takes another twenty-four hours—Holy Saturday—to travel back up to the earth’s surface, like Christ laid in the tomb all of Holy Saturday.

Before, like Christ resurrects at dawn on Easter Sunday, popping back up to the earth’s surface, to begin his ascent up Purgatory, on Easter Sunday morning.

III. Vico... cthonic heroes

Dante’s project, and for that matter the story of Christ, concerns, above all, the idea of incarnation. That is, the divine in man.

In line with the Medieval troubadour love poetry tradition Dante comes out of, it is the mystical beloved he describes who becomes the Christlike incarnated one; it is through the description and deification of, in Dante’s case, Beatrice, that an entirely new kind of incarnation—the perfection of the divine, mixed with the particularity of the human—exists in a single form. This is the subject of Dante’s early book Vita Nuova, written about Beatrice before her untimely death at age 25, a series of poems loving her and elevating her to a divine status.

And the story of Christ, as Auerbach explains in his 1929 book Dante: Poet of a Secular World, marks the shift in human consciousness where the divine, previously something above and outside of man, incarnates into man; more, into a common man, who takes common men—fisherman and publicans—as his disciples, and as a literary work includes incidental encounters, as it were extras in scenes previously populated entirely by semi-divine protagonists with fixed fates. The gods and heroes in Classical myth played out fates inherent to their character. Aeneas marked a shift, since he is told by the Gods that he has a sacred mission (to found Rome), and must carry out that mission, a hitherto unheard-of idea, of a common man serving as a vessel for divinity. Dante continues this progression of expanding the breadth of people allowed to be included in the drama of divinity—Dante, the storyteller and protagonist, is just a regular guy claiming that this supernatural journey happened, that with his own eyes he saw his sacred vision.

Dante claims, on the one hand, that those who, hiding behind positions of divinity, act in base, selfish ways, are the most unforgivable sinners—those who pridefully believe they are divinely ordained but are not. At the same time, Dante believes that the divine, through proper humility, contemplation, love and knowledge can radiate from and flow through the flesh.

Of course, how could he not think that, if he considers himself to be a sacred scribe—a vessel for the Holy Spirit to flow through him.

The audacity of Dante, what Goethe, in 1821, described as his “repulsive and often disgusting greatness,” (Mimesis, 185) is how far he extends the reach of the divine into the incidental and the everyday. For Dante, it’s On this day, in this specific year, that I looked over my left shoulder, and I promise you, reader, I saw this—something he obviously didn’t see. Putting his most random contemporary right next to the most mythical archetype. And yet, despite this bravado, Dante emphasizes that contact with the divine is about humility; he frequently quakes with fear at what he’s seen. If done correctly, one’s association with an older, archetypal story is an act of humbling, a submission of yourself beneath something higher, a recognition of your cosmic smallness. Which then, through faith, becomes something you can bind yourself to (religare, literally to bind).

*

This progression Auerbach charts only really started to make sense to me once I traced his research back to who he was reading. How did the notion of the divine, something higher than man, that man must humble himself beneath, begin in the first place?

Writing four centuries after Dante in Naples, right up until his death in 1744, Giambattista Vico (b. 1668) charts the roots of this connection, implicitly tying the Christ story to the first myths, the first heroes. Vico, who Auerbach spent ten years reading before writing his book on Dante, and who Joyce read to write Ulysses and Finnegan’s Wake, in his New Science (1744), explains anthropologically the origins of the human orientation towards divinity, towards something higher, and shows how this impulse led to the organization of civil societies, which are distinguished foremostly as those humans who began practicing the rituals of marriage and burial.

He explains the origins of the human orientation towards divinity as follows:

In the beginning was the universal flood, related in all the foundational myths, at ~4000 BC; and then it was the first humans, roaming the primeval forest, foraging and killing and taking whatever they wanted, then fleeing to the next cave-shelter they could find. There was no reason to stay put, to act outside of one’s immediate urges. No such thing as Time, since there was nothing to mark it with (no harvests). There was no writing, since humans had to flee constantly to find new meals, new shelters.

Man needed something higher to humble him, and a reason to be humbled. This, Vico argues, was the weather. Thunder and lightning. Various thunder and lighting gods developed in various foundational peoples—various Jupiters. And it was the advent of agriculture that led to humans having something to fear, when the weather got bad. They had to protect their crops. They weren’t merely fleeing to the next cave. Years began to be measured by harvests, and humans for the first time stayed put and waited out the dark times, the winters with no crops, rather than fleeing. They began praying to the heavens for the sun to return from above, and for the seeds to sprout up from below.

They began changing their behavior, not simply acting on their immediate urges. They began to practice marriage, the custom of choosing a particular woman, now that they lived in a particular place. They began to practice burial, consecrating their dead rather than leaving them out in the primeval forest like compost. This led to telling stories about the dead. This is why the earliest texts consist largely of lists of marriages and deaths (the Old Testament).

Next humans looked to heroes as divine, not simply humbling themselves beneath the weather, but beneath an individual archetype who went into the unknown, outside of the visible domain, and did a courageous act that led to the okay-ness of the group. The story they brought back and told would get retold. Hercules is the earliest example of this; the first of his twelve trials is to venture into the ancient forest to slay the Nemean lion—that is, raze the primeval forest to create fields for growing crops.

Spewing forth flames, this beast [the lion] set fire to the Nemean forest. When Hercules killed it, he donned its skin as a trophy and ascended to the stars. … this lion represents the great ancient forest of the earth, which was burned off and placed under cultivation by Hercules. (2)

We see that the divine hero, which is less an individual than an archetype of a neolithic hunter, must venture beyond the domain of the group, into the darkness (like Christ enters the underworld), to achieve a task necessary for the survival of the group (razing the forest so they can grow crops; redeeming humanity from its fallen state) and then return to the group to tell of what he saw (as Christ is resurrected), at which point stories about him sprout up. He then ascends to the heavens (Hercules, in his twelfth of twelve trials, must venture into the underworld to face Cerberus, the three headed dog, before he can ascend to his rightful place in the heavens).

We see this concept continued in Virgil and Homer: the hero must fight the war, outside the domain of the group, that founds and protects the nation; and it’s symbolized by a descent underground, followed by an ascent up into heaven, like Christ descends than ascends, like Dante goes into Inferno and up to Paradiso.

And yet, this archetype is not brash: Hercules, like Christ, is symbolized by the courage to slay the prideful, and to protect the weak. If they didn’t act in this just way, it wouldn’t lead to the benefit of the group, and their stories wouldn’t be retold.

This is the tightrope Dante walks; claiming status as a sacred scribe, while maintaining his humility beneath something higher.

IV. Flying out… pulling up…

I fly to Rome on April 26th. It’s the date of the cheapest ticket listed in the window of dates Catherine gave me. A couple days after the other residents arrive. I’ll stay till May 9th.

On the flight, I read Canto X, the circle of heresy, in which Dante encounters the leaders of the political factions in Florence that led to the conflict that got him exiled. Both treat the rightness of their side with religious fervor. That is their sin. Neither actually care about the people, or establishing peace.

Like Dante idealizes Christ as the paragon of how to live as a man infused with the divine, Dante also idealizes Julius Caesar, and the Pax Romana he established up until 44 BC as the prime historical example of a just, peaceful leadership. He feels his exile is due to the greedy, corrupt successors of a once sanctified Church abusing their power, like Tiberius Caesar abused the power and peace his predecessor created, some 70 years later, when he crucified Christ.

It’s muggy and surreal when I step out of International arrivals in Rome. Like Aeneas touching down, back in Caesar’s domain. Just like I did three years ago—

I’d been awake almost twenty-four hours, it was a whole process to fly during that time, the day after Christmas 2020, arriving to JFK six hours in advance to get all my documents sorted, to prove that I was allowed to fly to Italy during that time, then another few hours after to go through the line to get tested once in Rome, everyone lined up to get that cotton swab jabbed into their nose by hazmatted health workers. I stepped out into that dank, cloudy morning to find Gian M-95’d, hunched and cheeky in his big-ass florally lapelled fur coat. Hugging him in a delirium, in disbelief that we’d actually pulled this off.

This time I walk right on through customs. I start to tell Catherine about all the synchronicities I’m feeling, revisiting this Dante. Not going too crazy, so she doesn’t think I’m totally insane.

And we drive south to Sezze, along the highway that runs parallel to the Appian Way, the earliest and most important road connecting Rome to Naples to Brindisi—

Gian drove casually along the water, parallel to the water, pointing out landmarks. This whole area, these lowlands, the Pontine Plains, he explained, was for most of time uninhabitable, due to being too swampy. Too wet to grow crops. It would get overrun by mosquitoes, drawn to the muck, and people traveling to and from Rome would get bitten and die of malaria.

Julius Caesar, it was said, had plans to irrigate it and make it suitable for crops. But it wasn’t, interestingly enough, till Mussolini exercised his unilateral power to make it happen, that the area got drained.

Sometimes it takes unilateral, tyrannical power to get something that needs doing done; and yet, it’s so rare that unilateral power remains untyrannical.

Gian was the last of his kind. A unilateral leader, he responded only to his own taste. People looked to him for what was good, and he simply made things happen when no one else could. And it was respected and venerated, because he wasn’t acting selfishly, he cared about what was good for literature, and he did what was good for literature.

Catherine and I stop at the mozzarella shop we went to last time, one of the few places we went with all the restrictions. There were yellow days, red days, green days, seemingly arbitrarily controlling civilian movement. They’re out of the mozzarella we want to get. They make it fresh every morning, and every day it sells out. We settle for a smoked version.

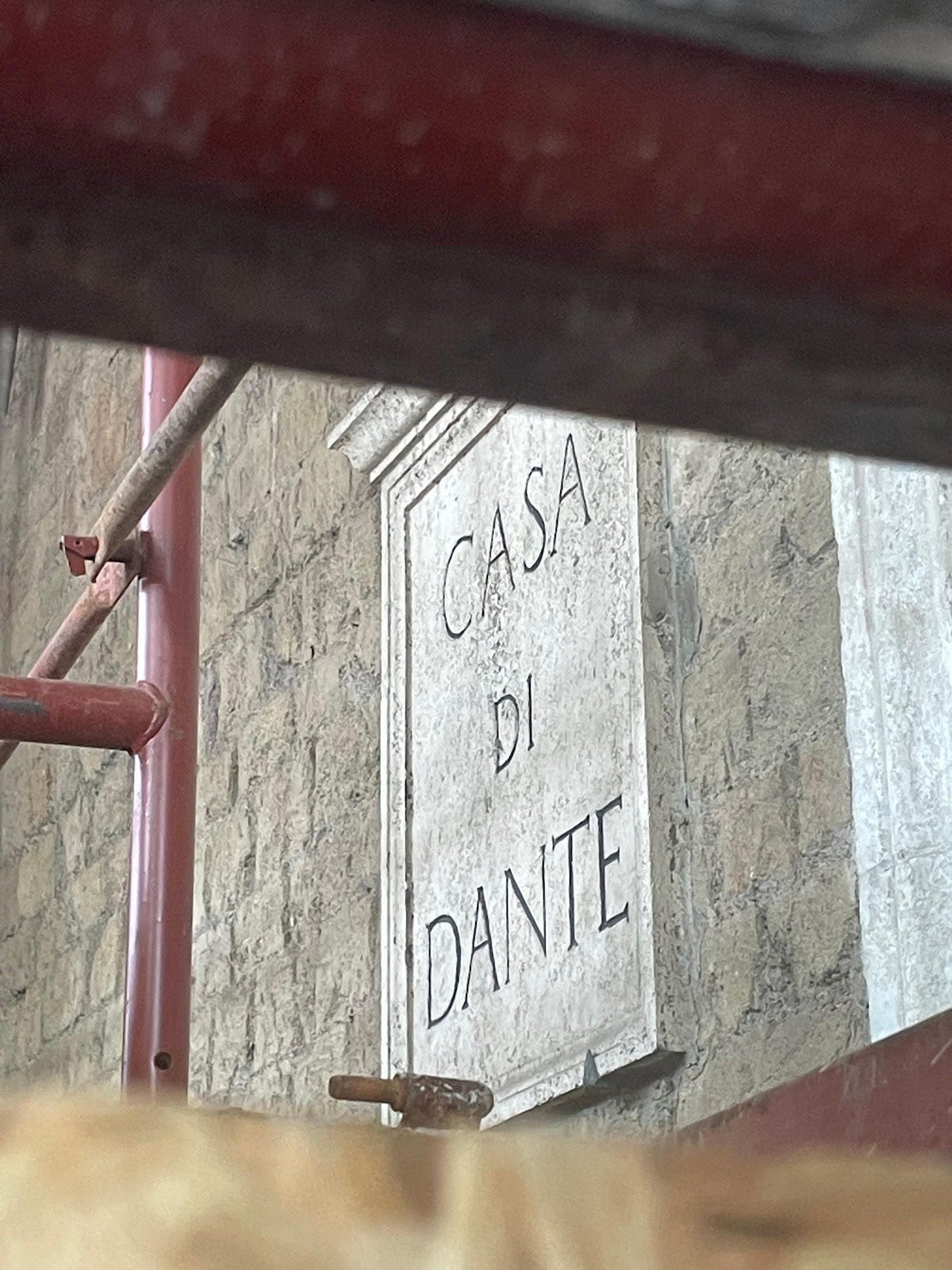

The property sits regally atop a hill in the center of Sezze. Pulling up to the entry gate like Dante pulling up to the first circle: it’s now the Giancarlo DiTrapano foundation, there’s a new plaque. I get flooded with memories and intuitive nudges. Catherine drives up the hill, and shows me my spot. It’s in a side house, set off from the other residents. Where Gian used to go to be alone and think. There’s a huge poster over the bed of an old Tyrant Magazine cover, a play on The Smith’s album The King is Dead, except it says The Tyrant is Dead.

Giu, Gian’s widower, whom I haven’t seen since that last trip, is out at work.

I drop my bags and Catherine says take a shower, do what you’ve got to do. I’ll be up at the house.

There are all these plants on the side of the hill out the main window, and then there’s a porthole at the other, with no screen, that I open for a cross breeze. Pollen blows in through the window. Out of it you can see the Tyrrhenian sea off in the distance, some six miles down the way. And a small protrusion, Circeo Mountain, a hill on an inlet Odysseus mistook for an island. It’s Circe’s Island, where Odysseus gets stuck for seven years before finally being allowed to leave on the condition that he venture into the underworld.

I walk down the hill, out the gate and into town. I sit on a bench and open Dante. I’ll greet the rest of the residents once I return.

I wouldn’t know this before, and I’ll be shocked to learn this in some months, but Sezze, as legend has it, was founded by Hercules. After fighting off the Lestrigonians down in Sicily, he traveled up here, and settled in these very hills. Sezze’s town crest, in fact, is Hercules slaying the Nemean lion.

I’m in Canto XII, and Dante and Virgil transition from the sixth to the seventh circle of hell, which marks the shift from sins of Incontinence (sins of passion, or heightened appetite) into sins of violence (intentional, willful behavior). They’re in the circle of Anger, and are scaling a rock face, when there’s an earthquake. Virgil tells Dante about “the other time I came down into nether Hell this rock had not yet fallen … it was just before He came who carried off from Dis the great spoil of the highest heaven.” (Inf. XII.34-39)

Virgil is referencing the earthquake that happened during the crucifixion, that shook the tomb open and allowed him to resurrect. Virgil would have been in Limbo, as a Pagan who died 19 years before Christ.

The Christ story participates in the pagan notion of the divine being associated with higher, divine auspices; it’s an earthquake that, like thunder and lightning—nonhuman rumblings from above and below—humbled the first humans. Only, now, the divine auspice is associated with a man.

Back up at the house, I greet the rest of the residents. Over dinner, I try to explain all the things I’ve been feeling and thinking, but my words fail me. Giu shows up right as we’re wrapping up. It’s good to see him again.

V. The first morning…

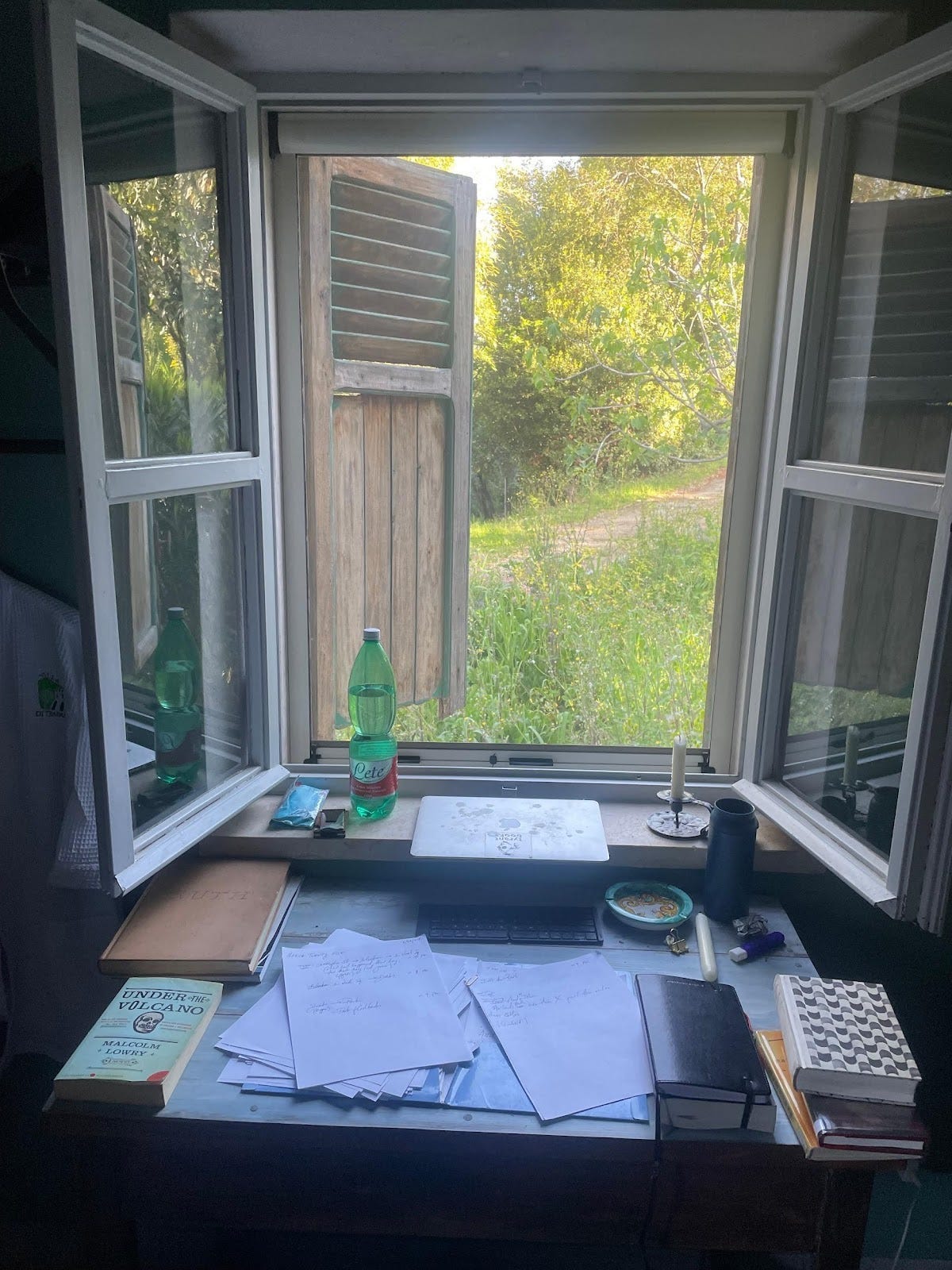

The first morning I’m up at five a.m. I arrange my desk, facing the window, lay out all my papers and get to work.

I try to assume a perfect state of concentration, there’s no Wi-Fi in the room, and my international phone plan is slow. Like St. Benedict on Saturn, the seventh circle in Paradise, like I’m assuming a perfect state of contemplation (though I won’t have a clue about this yet). I work till noon, then need to move. It’s hot as shit out. I bring Dante with me and head down the hill, shortcutting down the steps rather than taking the winding path, out the front gate and to the park at the end of the main drag there. Past the roundabout. It’s a bit overgrown and a free for all—trash strewn here and there, evidence of teen loitering, drinking, on the thin grass around the benches.

I find a bench and sit.

The number of the Canto, XIII, strikes me as menacing somehow, how it looks at the top of the page. Sitting there amongst the trees, a foursome of non-Italians in rhinestone tees and with skin fades across the way, lounging and sipping tall Stella’s, I open my book and read.

And it takes me a sec to realize what I’m reading.

We’re in the second ring of the seventh circle. Violence—wilfill, deliberate. The first was violence against others. This is violence against the self.

Virgil and Dante, as soon as they enter, get hit with the Harpies, the half bird, half woman monsters who attack Aeneas and his men on his way to Rome from Troy, via Carthage, where he falls in love with, and then leaves, Dido. Aeneas doesn’t know what happens to her after he leaves. He’s just traveling along, and gets attacked by the Harpies, who hit him with “doleful prophesies of woe to come. They have broad wings, human necks and faces, taloned feet, and feathers on their bulging bellies. Their wailing fills the entire trees.”

I’m sitting here in this park, and the trees around me look doleful and sad.

Aeneas must then go into the underworld. In order to enter, he snaps a golden bough off a tree.

Here, Dante snaps a twig off the tree, despite Virgil’s warning not to, “that his present thoughts will be cut short,” and the stem cries out, “Why do you break me?”

It’s Pier della Vigna, a trusted confidant of Emperor Fredrick II who, accused of treachery, was thrown into prison and blinded; soon after he committed suicide.

Virgil asks if they’re ever set free from being turned into a tree for committing suicide.

Dante writes, “When the ferocious soul deserts the body after it has wrenched up its own roots, Minos condemns it to the seventh gulch. It falls into the forest... Terrorized by harpies, they must drag their bodies for eternity.” (XIII.94-108)

I feel totally unsettled. My body tensed, blood rushing to my brain.

I put the book down, walk deeper into the park. I’m surrounded by trees. I can only hear voices all around.

Aeneas, too, encounters the suicides on his journey into the underworld. When he comes upon “those who, although innocent, took death by their own hands; hating the light, they threw away their lives. But now they long for the upper air, and even to bear want and trials there. But fate refuses them: the melancholy marshland, its ugly waters hem them in.” (VI.573-580)

And he’ll come upon Dido, whom Venus, with the help of his son Cupid, will make fall in love with Aeneas in Carthage, where he washes up on his way to Rome. They’ll spend some time together, and Dido will be smitten, want him to stay through the winter. Till Jupiter learns of Cupid’s trickery and grows angry that Aeneas is going against his Fate—he must start Rome, this will lead to the Pax Romana, the time of Julius Caesar, where the world, at least for a time, will be ruled in peace, with divine justice, laying the groundwork for the birth and crucifixion and resurrection of Christ, redeeming humanity.

Dido, though, knows nothing of this. She simply wants to spend the winter with her love Aeneas, who showed up out of nowhere and who gave her a renewed sense of hope ever since her first husband, Sychaeus, was murdered by her brother.

So when Aeneas tells her he must leave, indeed leaves with almost no explanation, simply “since Jupiter—the gods—told him to,” she falls into a rage, curses him, and slays herself. “She died a death that was not merited or fated, but miserable and before her time and spurred by sudden frenzy.” (IV.958-961)

I think about how, on that fateful 2020 winter solstice, right when Gian finished the final version of Fuccboi, and I was preparing to fly out to Rome, Kyra fell into one of her depressive states. Into “a sudden frenzy.” I didn’t know what to do whenever this happened. Especially with the task I had before me—somehow defying the powers that be, that said we had to stay locked inside. We, Gian and I, had start this new press, to found a new city. I just sort of shut down. This was the same type of state she fell into the night she died.

Unlike in Purgatory, where they know they’ve done wrong, and in Paradise, where they’re exemplars of the right, in Hell, no one can admit that they’ve done anything wrong. They’re fully in denial, justifying what they’ve done, blaming others.

VI. Fossanova…

I stay up damn near all of the first three days. No matter how late I stay up, drinking and talking with the other residents, I awake at the same time. Five a.m. Sometimes 4:55. Point being, I must be up at five, at my window, writing. Reading. Working. Up at the house, I joke that Gian’s spirit is waking me up. Telling me to get to work.

On Sunday morning of the third day—Eastern Orthodox Palm Sunday—I get a notification in the group chat that some people want to go to mass. I’m in a groove, I consider staying. At the last minute, I throw on a button up, tuck it in, untuck it again, and bound up the steps just as the cars are pulling out. I ride with Giu.

On the way, he expounds on what Gian told me last time about the swamps.

I remember the story, but I let him tell it again, feeling like time is a spiral.

I learn a new detail: what took them so long was, they kept trying to irrigate it perpendicular to the shoreline. When what they needed to do, counterintuitively, based on the physics of it, was dig parallel.

~

It’s an astounding church. Fossanova Abbey, just down the way from Sezze.

We stand in the farthest back pew of the stunning, vast space. I can’t understand the mass, but I pick up some words.

After, Giu leads us on a tour through the belly of the chapel. Into an inner sanctum, trees in the middle, two circular areas that run around it, one covered, one not, for Benedictine monks to pace around, rain or shine. He leads us up some steps to Thomas Aquinas’s tomb.

Dante will encounter Aquinas, the Dominican friar born in 1225, right before Dante’s time, in Paradiso X. The didactic aspect of Dante’s work is drawn heavily from Aquinas’s teachings. It was a comment Aquinas made, about poetry serving no moral instruction, that pushed Dante to write his poem how he wrote it.

To return to the question of the possibility of incarnation—of the divine to exist in and through man—if we ever left it: through Inferno, we encounter a series of historical and mythical and contemporary characters, all of who committed some sin, in ascending order of greater sins: we have Popes, corrupt clergymen, diviners and deviants, etc. We have those who thought they were doing right, who thought they were divinely inspired.

In Purgatory, everyone encountered knows they’ve done wrong, and are repenting for their sin. If they manage to repent sufficiently, they’re led to the next level.

But in Paradise, we encounter, in the final four of seven planets, starting with the sun, exemplars of real life people who, as Dante saw it, lived their lives on earth in a divine way, according to the trait of the specific planet. On The Sun we find exemplary divine knowledge; on Mars, exemplary war; on Jupiter, exemplary divine rulership; and on Saturn, the last planet and first pagan god, exemplary divine contemplation (St. Benedict, the monk the monks here at Fossanova followed).

Aquinas, in Canto X, exemplifies perfect divine knowledge. Aquinas, who died here at Fossanova, in 1274.

Dante starts out Canto X: “Gazing on his Son with the Love the One and the Other eternally breathe forth, the inexpressible and primal Power…” (Para. X.1-3) This cryptic passage, believe it or not, communicates something deep. It has to do with the Holy Trinity. The “inexpressible and primal power” is the Father, or God. The “love … eternally breathe[d] forth” is the Holy Spirit. And “the one and the other” means the father, or God, and the Son, or Christ—what the Holy Spirit flows through. This was cause for much contention, and in fact is the main reason for the split between Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox Catholicism. Since the council of Nicea in 325, the Eastern Orthodoxy maintained that the Holy Spirit, God’s love and wisdom, can flow only through the father.

It was Eastern Orthodox Palm Sunday now, three years after I last spoke to Gian. And here I see Aquinas’s tomb, a man who, like Dante, believes the Holy Spirit can flow directly through the son.

The implications this has, in terms of man’s ability to act with direct divine guidance.

What’s spookier is, Aquinas was “summoned to defend [this position] against the Greek deputies at the Council of Lyons in 1274…” (X.1-3, notes)

He was on his way from Naples, walking with his donkey, along the Appian way, to defend the idea of the son’s ability to channel the divine directly when… he got overcome by an illness and died!

Damn, I say to Walt. He got bit by a mosquito from the swamps.

Thought the Holy Spirit flowed through him, but God thought otherwise and got him!

~

The next morning, something hits me. Something’s off. I’d noticed something the night before, how my face was feeling. My face was feeling off. My eye. Something wet and weepy. I fall asleep reading the next canto, the sexual deviance canto.

I wake up and my eye is sealed shut. Red and swollen and ballooned.

There’s something weird about this. This hasn’t happened to me since the time of the book that I wrote, that I worked on with Gian, the book that’s about a death and a resurrection.

This is what was happening in the timeline of my book. That the protagonist must heal is way out of.

I don’t have my meds on me, I packed the bare minimum. And the drug that I got on in order to resurrect me, again, in the time of the book, I didn’t renew, out of laziness. I’ve gotten prideful and slothful, thinking I’m no longer susceptible to the storms that are always liable to hit, it’s only when an empire or a nation or a body gets their defenses up so high that they start to think that they can play god, and abuse their power—thinking that the Holy Spirit flows through them directly, that they can do, eat, drink whatever.

I walk up to the house. Walt goes, Ohhh shit, bro. What happened?

I don’t know, I say. I think a bug or spider must have bit me. A mosquito.

A mosquito? Bro—you got Aquinas’d!

I head down the hill and walk into the Farmacia. No one speaks English; one lady sort of does. I just walk up to the counter, point at my eye, and say, Antihistamines? People clear a path for me. She gives me some antihistamines. And also some prescription eyedrops, some steroid cream.

And finally—I’m literally replaying the time of the book—some internal steroids. Like I didn’t learn anything after all.

VII. Circe’s island…

On Wednesday, my eye has subsided some. Still very uncomfortable. I’m back at the park. I read my customary daily canto, and then, hit with a surge of feeling, roam to the edge of the park like I did before. I can see the ocean off in the distance, like a mirage. Last I came out here, that was one of the first things that Gian pointed out. Circeo Mountain. Where both Odysseus and Aeneas got washed up. It wasn’t an actual island, it just looked like one.

I consider walking out to it. It’s six miles. Walking up the hill, on the way back, will be brutal. I start moving, scaling the periphery of town, looking for a way down. It’s a steep switchback with guardrails, though I did see bikers biking it one of the days. I pass the road and end up at a church. I sit there at a bench out front while an African dude plays Afro pop songs on a bluetooth. An old Italian man sits on a bench, looking out at the ocean. He doesn’t seem bothered by the music. I initially am, then realize I kinda like it; I pause my music but keep my headphones in, pretending I’m listening to something else but listening to his music.

Circe lures people onto her island and turns them into animals. She feeds them the mystical mandrake plant, and they can’t resist her charm. They gorge themselves on food and drink and never leave. Odysseus is only able to resist because, wily schemer that he is, he is prepared with the counter drug. Still, he stays stuck there, on the island, for seven years. He’s only able to leave on Circe’s condition that he go into the underworld.

I don’t think I was as attentive to Kyra as I could have been last I was out here, in eyeshot of Circe’s island. It was so isolated and cold in the city, being locked down like it was, Kyra kept calling me I remember. I’d left her there all alone.

I decide I won’t walk to the island after all.

VIII. Naples / Cumae…

On Eastern Orthodox Good Friday, the property goes dead silent. My face is feeling a bit better. I baptize myself in the pool. My eye is still deformed. I look and feel like a primeval giant. I work through the morning, and then right at noon head up the main house to do my one duty—water the plants Giu said to water, that he’s trying to grow on this patch of dry dirt right by the entryway. I tend to my garden. Then head down the hill to read my Dante.

The next morning, we all get onto a train and head into Naples. Catherine has gotten an AirBnB. There will be a reading for the foundation that night, in collaboration with an Italian press. I’ve prepared a bit of new writing I’ve written, that Catherine got translated into Italian, so the audience can read them side by side. I’m trying to write about Her in a way that doesn’t presume to know what she was going through, to not reduce her to her final, impulsive act.

And it’s a route I took with Gian three years ago, down south along the water to Naples, and there’s this area right when you start to enter it, when the coast curves in a bit, and I don’t even realize we’re whipping it right by Cumae, past Lake Avernus, literally where Aeneas washes up in the beginning of Book VI, where he finds the Sybil and begs her to take him into the underworld.

It’s Orthodox Holy Saturday and we’re traveling right past the entrance to Virgil’s underworld, past where Dante’s “dark wood” of Maundy Thursday is based off of.

And I’m reading over the bit I’m going to read, a meeting between a Young Man and a Taken Woman, a woman with a Husband, how from the first moment, their fate was sealed, and—

The moment Aeneas and Dido mate for the first time, “confusion takes the sky, tremendous turmoil... lightning fires flash, the upper air is witness to their mating... and That day was her first day of death and ruin...” (Aen. IV.219)

And the moment Dido sees Aeneas’s ships leaving, because he must go to Rome, to found a new city, Dido laments, “And why was it not given me to lead a guiltless life, never knowing marriage, like a wild beast, never to have touched such toils? I have not held fast the faith I swore before the ashes of my Sychaeus.” (IV.762)

But pious Aeneas, following God’s orders, off to Italy to found Rome, doesn’t even know of Dido’s fate, not until, here at Lake Avernus, meaning “no birds,” since birds would die from the noxious fumes of the underworld, he finally enters, led by the Sybil, and encounters, there in the underworld, Dido herself. And to her he says, “Dido, is it true...? Did I only bring death to you? I swear by the stars, the gods above, I was unwilling when I had to leave your shores. But those same orders of the gods that now urge on my journey through the shadows, through abandoned, thorny lands and deepest night, drove me by their decrees—” he’s still moving quickly, he still must go soon, urged by the gods, even now—

And Dido, anyway, wants nothing of it. “She tore herself away; she fled—and still his enemy—into the forest of shadows.” (VI.621)

And that night I read the story I wrote, about the Young Man and the Taken Woman, I read last, and it goes alright, a bit of a let down perhaps, it’s not the upbeat stylish tone expected of me, it’s dense and thorny and heavy, it falls on deaf ears.

And we roam Naples, into the night, drinking Aperol spritzes till the wee hours.

And in the morning, on Easter Sunday morning, Catherine takes us to Capodimonte, the museum at the top of the hill in Naples.

And it’s like the garden of Eden at the top of mount Purgatory.

And the rest of the writers move through quickly, but I’m just overwhelmed by everything, I can’t understand what all is happening. I see a group of nuns and I follow them through, and on this day I learn more about March 25, I realize that’s also the day of the Annunciation, the day the Angel Gabriel told Mary she was pregnant, March 25 in the year 1, nine months exactly before Christmas, and it’s also that date because it’s right around the spring equinox, a time of supposed renewal, and no matter what type of hell you’re undergoing there must be a possibility for renewal, that’s the message of the Christ story, there must be a return of spring, right?

And that Monday we’re back in Sezze and all goes quiet and calm, and I return to the Dante, and I read Canto XXVI, and I’m just stunned to find Ulysses, that is, Odysseus there, Dante has placed him in there, just like Homer places Hercules in his Hades, and Dante fashions a story of Ulysses being a tempter, a fraudulent counselor, who, like the snake in the garden, tempted those around him to travel further than was humanly reasonable, than had ever been traveled, convincing a whole crew of men to forge their way to the ends of the earth, to eschew filial duty, his responsibility to Penelope his wife, in order to find knowledge and wisdom, only they push too far, a whirlpool hits, and takes out his entire crew—

Odysseus told his crew they would find truth and beauty at the end, but they all died.

And in Hell he’s defending his actions, saying “It was their choice!”

And is that what happened, is that what I was doing, pushing the limits of storytelling, of doggedly creating art in a time when no one was, in a way no one had—

But of course isn’t that what Dante is doing, pushing the limits of language, creating a new language—

And that is what we were doing, Gian and I, creating a new language, not like Nimrod, who I encounter some Cantos later, who tries create a single language, to build a tower of Babel directly to heaven, only for it to all come crumbling down and scatter everywhere— (Gen. 11:1-9)

No, Dante and I, I thought, were doing the opposite, taking the scattered language, creating a new language that incorporated all languages, the high and the low, the vulgar and the refined—this is what Dante was doing, this is why Gian said what he said that New Year’s Eve toast he did, over the twelve days of Christmas I was here last, he said, To a new language, looking right at me.

But nonetheless it stuns me, reading this.

And I can’t help but think of Giu, how we haven’t been able to talk face to face, directly, about everything—

Till the last day, once all the residents have left, and I have forty eight hours on the property to myself, and it’s the Wednesday after Easter Sunday, in Dante’s time he’s in the garden of Eden, he’s said goodbye to Virgil and now Beatrice is leading him, and Giu says why don’t we go have a meal together, there’s town a few towns over called Cora, it’s the last night and there’s a storm hitting but we head there and we eat one on one, a good few courses, and we eat our fill and head back in the storm, in the dark.

And that night in Dante time Dante is going with Beatrice from planet to planet, on the sun he encounters Aquinas himself, Aquinas was Dante’s teacher’s teacher, and Aquinas gives a speech, and he exhibits astounding humility, he spends the first part of his monologue homaging his teacher, listing all his teachers, not puffed up with pride as Ulysses was, speaking only about himself, defending himself—

And if it’s a matter of whether you’re capable of having a divine vision or not, and Dante clearly is someone who believes that he is, then what a thin line it is that separates Odysseus from Aquinas, they both cross a boundary line, which echoes the boundary line crossed by Adam and Eve, Dante doesn’t single out Eve when he encounters Adam in Canto XXVI of Paradise, Adam is held responsible for the actions of Eve, and Adam is so calm when asked, somewhat rudely, by Dante, why he committed the sin that led to all of humanity being in a fallen state for 4,302 years (XXVI.119-20) until finally, on March 25 of the year 34, he was redeemed by the sacrifice of Christ. That most important love act, to know you are going to be betrayed, yet to go out and love your betrayers nonetheless. To accept everything that comes to you with love, even the darkest night of the soul where you are mocked and turned on and crucified. This redeems Adam, and Adam, in response to Dante’s question about it, addresses it directly, just says what happened.

Because what distinguishes Ulysses from Aquinas, the weather-fearing Pagans from the giants, Christ from Judas, is one thing: humility.

Mere man is capable, Dante believes, Aquinas believes, of having a divine vision, of acting as a vessel for the Holy Spirit, so long as he remains humble.

It is pride that led to the primeval fall—Satan’s fall out of heaven. He couldn’t handle that God was God, and that he wasn’t.

It is pride that led the giants to go against Jupiter—to defy the thunder and lightning.

~

I haven’t seen everything through, I’m into the giants (Inf. XXXI), about to enter Judecca, Judas’s circle (Inf. XXXIV), really still reeling about Ulysses, feeling like I’m the fraudulent counselor, guiding others to the ends of the earth no matter what, causing their ruin, when Giu says, Why don’t we go to Dante’s house, the house Dante exiled in, in Rome, on the way to the airport tomorrow.

Only he gets caught up with something, and he arrives much later than our meeting time, we might have to skip it, and we get back on the road, headed north to Rome, right along the path Aquinas was walking when he got bit by that mosquito, and we’re talking about Dante, and we’re talking about Dante’s rigor, his ambition, and we talk about Gian, how he was like Caesar, a tough but fair tyrant, irreplaceable, he has no successors, only heirs, heirs that needn’t be crowned, they’re implied, and we finally talk about what we’ve been ducking talking about all week, we talk specifically about it, and it’s so cathartic, and I love this man Giu, and we get closer to Rome and traffic starts hitting, and it’s a bit of a time crunch, and Giu’s going, I’m not sure if we’re gonna make it, and I go you know what let’s not, it’s all good, all week I’ve been ranting about Dante, pushing so hard about Dante, the other residents are tired of it, they think I’m tweaking, maybe I should let up on my mission to voyage to the ends of the earth to find truth, I’m thinking Giu thinks I was like Ulysses, pushing so hard—

But right when we’re about to abort our mission, turn off and head for the airport, Giu looks at me and says, You know what? No. Let’s keep going. We’re so close.

And we push a bit further and make it and it’s under construction but we give it a once over, and Giu tells me about the history of it, and we grab a coffee and we head to the airport train and it’s all good.

I give him a big hug and I thank him for everything and I get on the train and make my flight just fine.

IX. Ascension…

And on Thursday, May 9th, Ascension Thursday (or, in Eastern Orthodox time, the Thursday a week exactly after Maundy Thursday, that is, the day Dante encounters God himself in the final circle of Paradise, and then falls back down to earth, at which point he must translate all he’s seen) I fly out of Rome.

And late that night I stumble back to my apartment in Manhattan, all banged up, leaking out tears of disbelief or confusion or prostration, letting the warm rain wet the cracks in my roid worn skin.

And twenty-four hours later the sun rises anew onto the city, in through my window,

And twenty-four hours after Dante and Virgil manage to escape the final circle of Hell, jumping onto Satan’s tail when he’s not looking and climbing up the dark craggy cliff, higher and higher, navigating only by the sound of trickling water, they climb their way back to the surface of the earth, and up they sprout onto the base of the mountain of Purgatory, like plants after the long winter, and we begin Purgatory, the process of purification, as the sun on Easter Morning rises, Christ has risen, and who do we find here in the first Canto but an unlikely placement, Cato the Younger, the third betrayer of Julius Caesar, only unlike the other two, he’s not in the final circle of Hell, he’s at the entrance of Purgatory, even though he’s a suicide—he betrayed Julius Caesar, and then “resolved, rather than fall in Caesar’s hands... [to] put to an end his own life, after spending the greater part of the night in reading Plato’s Phaedo on the immortality of the soul,” 46 years before the birth of Christ,

Only his suicide, unlike Pier’s back in Canto XIII, is redemptive and Christlike rather than destructive, it’s an act he decides to do on his own for the freedom of the people.

And Virgil introduces Dante as a man who “has not yet seen his final sunset, but through his folly was so close to it his time was almost at an end,” clarifying the implication alluded to in the opening lines how down bad Dante was in that dark wood, “the straight way lost,” “so bitter death is hardly more so—”

And Virgil asks Cato about his wife but Cato, Hollander notes, “unlike Orpheus, will not look back for his dead wife.” (I.85-90)

And so Dante has now dug himself out of that state he was in on Maundy Thursday eve, they travel along the lonely plain, and they come “to the empty shore. Upon whose waters no man ever sailed who then experienced his return,” (I.130-2) they’re just like Ulysses, traveling along seas never traveled, telling a story never told.

And they turn the way Cato directs them, to the entrance of Purgatory, so they can begin the long process of climbing that mountain, of humbling themselves, and they, like Aeneas must do at the entrance of Cumae, pick from the plant, like Aeneas picks the Golden bough to offer Persephone.

Like the tree branch Dante plucks back in Inferno XIII, in the sixth circle of hell,

Only this time he isn’t hurting anyone, the branch doesn’t yell in pain, it simply, humbly, miraculously sprouts back,

And “what a wonder it was that the humble plant he chose to pick sprang up at once in the very place where he had plucked it.” (I.134-6)

Inferno XXI, 112-114: “Yesterday, at a time five hours from now, it was a thousand two hundred sixty-six years since the road down here was broken”—1300–1266 = 34 AD.

Damn. one of the best things about Dante and Italy I’ve read ever. And all this time I ignored him because of Rod Dreher. I’ll have to buy your book once I hold up the gas station and get the $.

clear & graceful & grand like the dolce stil nuovo 💯