DIANA AT NEMI — THE KING OF THE WOOD — THE GOLDEN BOUGH — AQUA ET IGNI — MORE VICO — DANTE MEETS PRE-FALLEN EVE, BEATRICE, AND CHRIST IN THE GARDEN OF EDEN AT THE TOP OF MOUNT PURGATORY

Friday, March 7 (cont.)

At noon I finish my maiden reading of Book IX of Paradise Lost and head down to the house to take Lila to the reservoir and give her a long walk. This is part of my groundskeeper yurt duties, you can’t have a savage uncivilized man lurked up in the woods with no duties, no woman around to civilize him. I bring my water jugs down to the house and fill them up, at the communal perennial spring of Eric’s kitchen tap, I’ve got to make sure I’ve got enough water to make it though the night.

The Golden Bough is so damn long I had to go back to the beginning to re-remember how the book started. To see what got its author, JG Frazier, hunting down these old myths in the first place.

It all started because one of the sacred rites in Roman mythology didn’t seem to cohere with all the rest. It seemed too savage, and to harken back to earlier traditions, wedged into Ovid and Homer and Hesiod out of place. This is the ritual of the goddess Diana at Nemi, a lake south of Rome, in her sacred grove, where Diana, or Artemis (or, recalling Vico, Persephone herself), the goddess of hunting and fertility and sometimes the countryside, in short, birth and growth, is characterized by some strange practices that Frazier wants to understand.

Diana of the Wood is accompanied by two minor deities, Aegeria, a nymph of clear, healing water, or the sacred spring that flows into the Lake of Nemi; and Virbius, or Hippolytus, who is Diana’s mortal male companion, is and in Ovid’s myth goes like so: Virbius spurned the love of all women, including Aphrodite, which leads her, scorned, to inspire his mother Ephedra to fall in love with him, but when he turns her away as well, she slanders him to his father, Theseus, and the slander is believed, and Theseus has Poseidon send a bull out of the sea to scare the horses of Virbius’s chariot, leading them to drag him to death. He’s Diana’s favorite though, so she brings him back to life and hides him deep in the woods, in a secret grove, where he reigns, hidden from Jupiter’s wrath, as king.

Here we have the mortal man loving the divine goddess, being killed and brought back to life (like Adonis is with Persephone and Aphrodite). Like the Troubadour love poet tradition Dante resuscitates is, or mere mortal man ascending the heavens, led by his divine beloved (the divine goddess, Beatrice)—though not, notably, as common Christianity is, Eve is not deified, she’s still held accountable for original sin.

But that’s the myth.

The ritual practice of the same story that JG Frazier is shocked by and seeks to dig deeper into the archaic practices it came from, is how, in the tree grove at Nemi, the Virbius corollary, The King of the Wood, is a position of priesthood that involves guarding the sacred tree from which no branch may be broken, and whoever holds this position remains priest-king till he is killed, allowing a bough to be broken off the tree, and then is replaced—the position is held by whoever holds it, until he is killed and replaced—and what’s more this bough that’s broken off the tree is the basis, so common knowledge goes, of the Golden Bough Aeneas breaks off to enter the underworld in book six of Virgil’s Aeneid (the basis of Dante’s Inferno).

This rite seems connected to the myth of Virbius’s premature death and resurrection, or vice versa, but JG Frazier senses this comes from older practices, the ritual regicide, the priest king of the Wood, the guarding of the sacred tree, the goddess of the sacred spring, and another characteristic I didn’t mention, of the eternal fire tended to by vestal virgins—these practices are found in various cultures throughout history, and JG Frazier finds all these examples of variations of it.

But most importantly it’s what it has to say about the Fall, and Christ’s killing and resurrection, and mortal man loving a goddess, and the challenge of marriage and fertility and death and renewal…

Milton, as we have seen compares Eve to not only Persephone but also Delia, or Diana, and even to her wood nymphs, who turn into the trees they tend to like Pound’s tree-girls, and but as Vico says, Persephone is simply the agricultural, underground iteration of Diana, the goddess of springs, or the original underworld, while Artemis is the Diana of the woods, or of hunting (Diana is in the heavens).

And, too, we have Satan, like the serial regicides of the priest-king of the wood, as the usurper of Adam, who plucks from the forbidden tree—the apple and the golden bough, respectively.

The difference is, with the Fall of Man, as interpreted in common Christianity, Eve doesn’t resurrect come spring like Persephone does for the sin of eating the forbidden pomegranate fruit; she causes humans for all time to live in a fallen state (till Christ resurrects to redeem Adam, though Eve remains to blame—outside of the apocryphal version of the story which includes Christ’s forgiveness of Mary Magdalene, a tradition Dante continues by deifying Beatrice, that Joyce and Faulkner continue in forgiving and redeeming cheating Molly Bloom and incestuous love child of Caddy girl-Quentin, who like Mary Magdalene is turning tricks with men sneaking into her window, till she escapes, or resurrects, on Easter Sunday morning)… But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Diana, according to Vico, is the third major deity the theological poets invented, as man stopped their wandering and began practicing the sacred rites of marriage and burial. The first was Jupiter, or thunder and lightning. The second, Vico says, was the eagle, the bird of prey associated with Jupiter, who led pious strong men to “lands on mountain heights, where the air is breezy and salubrious,” to “lands near perennial springs, which are most commonly found in the mountains.”1

“Near such springs, birds of prey make their nests, and hunters set their nets. … why the ancient Romans called any bird of prey Aquila, eagle, from aquilega, water seeker” (aquilex means a diviner or bearer of water)…

The first people, when they’d get terrified and humbled by Jupiter’s thunder and lightning, would then look to the sky, “and when they followed the eagle’s flight, they discovered perennial springs.” And so they venerated eagles as the second major deity.

And once they found water, they’d deify the goddess of springs, the underground deity from whence the water sprung. “At this point, people imagined the third major deity, which is Diana. She represents the primary need for water, which the giants get once they had settled on certain lands and united in marriage with certain women” (222).

And from here you have marriage, burial, family, communities—indicated by those who share water together.

Marriages were celebrated by water and fire, “aqua et igni, because the first marriages were naturally contracted between men and women who shared common water and fire.” (221)

Diana, who naturally was Jupiter’s daughter, was the first goddess of the springs, or the underworld, since primeval humans needed to settle near a spring to stop their wandering, needed water and fire to convince a woman to marry them, and so prayed and sacrificed to the goddess they invented who represented the continuation of their access to water.

Not the full answer, but germane to JG Frazier’s question of the strange rites of Diana at Nemi, the goddess of the spring, the serial regicide (or serial sacrifice previously) of the priest king of the wood who guards the sacred tree, looked upon by the goddess of the perennial spring, the vestal virgins who tend the eternal sacred fire.

*

And so off they go, “the dire snake, into fraud / Led Eve our credulous mother, to the tree / Of prohibition, root of all our woe,”2 and Eve is scared, but Satan convinces her, “ye shall not die: / How should ye? by the fruit? it gives you life / To knowledge” (686-7), and anyway god made you, he’s not gonna kill you, he says, “ye shall be as gods, / Knowing both good and evil as they know,” Satan says, “Goddess humane, reach then, and freely taste” (pause), he says.

And “into her heart too easy entrance won” (IX, 734), and noon draws near, and Eve must return to Adam soon, and she reasons, well the serpent didn’t die, he was irrational till he ate, and “So saying, she rash hand in evil hour / Forth reaching” she plucks and eats, and “Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat / Sighing through all her works gave signs of woe, / That all was lost” (780-5), like when Aeneas first copulates with Dido in Carthage on his way home to found Rome, and lightning flashed and the earth shook, and that was the first day of death, the first cause of woe,” since Dido is betraying her dead husband Sycheous, smitten by Aeneas, and will plunge to her own death once Aeneas leaves and she realizes what she’s done (like too Anna Karenina plunges to her own death once she realizes), and just like that Satan the Serpent slithers away and disappears, and Eve is euphoric as if drunk, and after a time she debates whether she will tell Adam, she wonders if god will punish her with death and if Adam will replace her, she thinks he’ll be “wedded to another Eve, / Shall live with her enjoying, I extinct.” But then she also thinks “I love him, that with him all deaths / I could endure, without him live no life” (IX, 833).

And there Adam waits at high noon, Adam who while waiting “had wove / Of choicest flow’rs a garland to adorn / Her tresses, and her rural labors crown, / As reapers oft are wont their harvest queen,” the most explicit if indirect Persephone reference, and not only Persephone but the corn maiden rituals the story of Persephone mythologizes, preparing Persephone the harvest queen’s flower garland, Adam like the harvesters awaiting Persephone’s return from Hades come spring, Persephone who is Diana, goddess of springs but also of countryside, of fertility—her rural labors.

And Adam immediately senses something is off, and “in her hand / A bough of fairest fruit that downy smiled, / New gathered, and ambrosial smell diffused,” like Aeneas plucks the bough to enter and return from the underworld, Eve does the same, returning from doing whatever she got up to with Satan down there, and she tries to apologize, she tells him how much she missed him, she tells him the tree is not dangerous, it opens your eyes, to see what god sees, you must try it.

And Adam, “amazed, / Astonied stood and blank, while horror chill / Ran through his veins, and all his joints relaxed; / From his slack hand the garland wreathed for Eve / Down dropped” —unlike Persephone and the corn maiden who is celebrated and crowned upon her return from Hades, Adam drops the garland he made for her, he’s speechless, “How art thou lost, how on a sudden lost / Defaced, deflow’red, and now to death devote?” For she is not simply the pagan symbol of fecundity, she herself is the fairer flower, and she has been deflowered, and so man has fallen.

And Adam considers what will happen, whether he’ll have to give up another rib to create another Eve, Eve says trust me, the fruit isn’t bad, have some, and she presents the bough of the forbidden tree with fruit on it, and Adam resists, “he scrupled not to eat / Against his better judgement, not deceived, / But fondly overcome with female charm,” gets you every time, that female charm, and “Earth trembled from her entrails, as again / In pangs, Nature gave a second groan,” again like when Dido’s impending doom is sealed, when she betrays Sycheous and lays with Aeneas (Book IV), and the sky thunders, and having given into their mutual wrongness, “As with new wine intoxicated both / They swim in mirth … Carnal desire inflaming; he on Eve / Began to cast lascivious eyes … in lust they burn” (IX, 1008-1015).

And so they fuck, and everything is amazing.

And then they come down, and discover they are naked, full of shame.

And they find the fig tree and pick big leaves and cover themselves.

And then they fight—“not only tears / Rained at their eyes, but high winds worse within / Began to rise, high passions, anger, hate, / Mistrust, suspicion, discord, and shook sore / Their inward state of mind, calm region once / And full of peace, now tossed and turbulent.” (IX, 1121-1126)

And Adam says if only you listened to me, did as I told you, instead of giving in to this “will of wand’ring” this morning, like the beasts of the plains wander, rather than stay put and await the harvest come spring,

And Eve says what am I, still your rib? I can never leave your side? If so, “why didst not thou the head / Command me absolutely not to go… Hadst thou been firm and fixed in thy dissent, / Neither had I transgressed, nor thou with me” (1155-1161), recalling how Anna insists, despite Vroksy’s warnings, on going to the concert, though surely she will get shamed and humiliated if she does (for being an adulterer), and then she does get shamed and humiliated and it’s terrible and when she returns she tells Vronksy, Why didn’t force me not to go?

And Adam says I warned you, I foretold what would happen, “and perhaps / I also erred in overmuch admiring / What seemed in thee so perfect… I rue / That error now, which is become my crime, / And thou th’ accuser” (IX, 1177-1182).

And “Thus in mutual accusation spent / The fruitless hours, but neither self-condemning, / And of their vain contest appeared no end”—both stuck in stubborn pride, blaming each other, neither able to accept that they did any wrong—like everyone in Dante’s Inferno is, unable to admit that they sinned, making excuses, blaming others, a living Hell.

*

But maybe this is the true beginning, the start of humanity, of the work, the arduous ascent up Purgatory, of having and losing everything, being crowned the king of the wood then usurped and killed and eaten, scapegoated, scourged ritualistically by the Group, this is the seasonal process, the serial regicide Theophagy—

On Saturday and Sunday I get up and do my tasks walk Lila perform my ablutions refill my water from the sacred spring, fill my barrow full of wood, return to the woods, maintain my eternal fire—

And on Monday it gets a bit warmer, and on Tuesday it’s like this, like spring,

And where else could we end but with Dante.

For Dante, too, has been regicided, exiled, he humbles himself beneath Virgil, he sets out on embarks underground on Good Friday morning, through the gate of Dis, in the year 1300, like Orpheus like Heracles like Odysseus sent by Circe to go see Persephone, he harrows hell for twenty four hours over 34 cantos till he descends into Hell’s final circle, Judas’s circle, where he encounters Satan himself,

And then like Christ like Persephone he pops up at the base of Mount Purgatory Easter Sunday morning, and Virgil leads him up the seven sin-tiers, pride envy wrath sloth greed gluttony lust, only the occupants here, over these 33 cantos, know they’ve sinned, are repenting their sins, and only then, finally, can he encounter his Beatrice, his divine beloved, returned from the dead like he ascended from hell.

And where else would this sacred meeting happen, there at the top of the mountain of Purgatory, but in The Garden of Eden itself.

And this is the point when Virgil leaves him, right as he’s about to enter the Garden, he says I’ve taught you all I can, he says “That sweet fruit which mortals seek / and strive to find on many boughs / today shall satisfy your cravings.”3

“Look at the sun shining before you, / look at the fresh grasses, flowers, and trees / which here the earth produces itself” (XXVII. 133-5) …

And Dante, himself like the self-seeding plants in the Garden can move alone now, his will has been strengthened by his long journey through Hell,

And he enters the sacred Garden and the plants are in bloom and fragrant and the clearest spring flows through it, and there like in a dream he sees “a lady, who went here and there alone, singing / and picking flowers from among the blossoms / that were painted all along her way,” (XXVIII. 40-42), and of course he like me like you just thought thinks who could this be, “You make me remember where and what / Proserpina was, there when her mother / lost her and she lost the spring” (XXVIII. 49-51), he thinks he’s Pluto and she’s Persephone, and that this is about lust, the circle of purgatory they’ve just exited, he thinks this is sexual, that she wants him to pluck from her, but no it’s not sexual, the lady simply turns in his direction, “lowering her modest eyes, as does a virgin,” (57),

She is pre-fallen Eve, she does not give into temptation, she stays tending the earth like god told her to,

And he’s not sure where he is exactly, and this prefallen Eve tells him,

Those who in ancient times called up in verse

the age of gold and sang its happy state

dreamed on Parnassus of perhaps this very place.

Here the root of humankind was innocent,

here it is always spring, with every fruit in seasons.

This is the nectar of which the ancients tell. (XXVIII, 139-144)

So it’s both the field where Pluto found Persephone and the garden of Eden that they find themselves in...

But Dante, unlike Satan, like Pluto, forestalls his lust, he doesn’t pluck the bough the apple the flower, he listens to this maiden, this pre-fallenEve, who leads him to Beatrice, the woman who died ten years prior to the poem has reemerged from the dead, joined by a procession of divine entities,

And they move, in a procession, through the garden

And they arrive at “a vaulting forest / emptied through fault of her who trusted in the snake” (XXXII, 31-32)

They come upon the tree of knowledge, barren and bare now, because of Eve’s sin

And Christ is there in the form of a griffin—half eagle, half lion, to represent his half divine, half human incarnated quality,

And then Beatrice descends from the Chariot driven by griffin-Christ, and “all of them murmuring ‘Adam’ / … they circled a tree stopped of its leaves / and any other flowering on its branches” (XXXII, 36-39)

And Christ is commended by all those gathered in the garden for restraining himself, for not plucking from the tree,

‘Blessed are you, griffin, for not plundering

with your beak this tree’s sweet-tasting fruit

that later wrenches bellies with its pain.’

Thus did those around the mighty tree cry out,

and the double-natured animal replied:

‘This is how the seed of justice is preserved.’

Christ being ‘the double-natured animal,’ speaks this final line, the only line he speaks in the whole poem—This, not plucking from the tree, is how the seed of justice is preserved.

And Christ then takes the staff or rod or cross or stick (bough) he’d been driving the chariot with, and ties it back onto the tree—

Turning to the shaft that he had pulled,

he drew it to the foot of the widowed trunk

and left it bound to the tree from which it came (XXXII, 49-51)

and this causes the tree to come back into bloom,

As our plants, when the great light falls on them,

Mingled with the light that shines

In the rays that follow the celestial carp [as when we go from Pisces (sign of the ‘celestial carp,’ the 12th of 12 signs), to Aries each year, the shift that marks the spring equinox, each time spring returns…]

Begging to swell their buds and are renewed,

Each on its proper color, before the sun

Hitches his steeds to other stars,

So, taking on a hue less red than roses

Yet deeper than violets, the tree renewed itself

Where its branches just before had been so bare

By tying himself to the tree—allowing himself to be crucified on the cross, rather than plucking from the tree—Christ redeems Adam

And this is the first step, binding oneself to the mast,

It used to be plunging underground and plucking from the tree brought gold to the lands and widespread acclaim for the hero,

Till Christ created a new type of heroism, of tying oneself to the tree, of accepting being scourged regicided reviled, of this having a regenerative humanizing quality to all—being a new type of Gold

And though this redeems Adam, of course Eve still remains at fault, and this is the apocryphal aspect, the thing that’s ongoing and still being asked, not simply how to redeem Adam but to forgive Eve, what Joyce attempts with Molly Bloom, what Faulkner does with little Quentin’s escape, what 2666 is about, a series of 300-plus unsolved rape murders no one cares to solve or stop, the ramifications of a society that never forgave Eve, that plucks and plucks from the tree till there’s nothing whatsoever left.

And it’s incredible what Dante has done, he’s suffused Christianity with its missing aspect, the archaic goddess worship, he’s expanded the idea of Christian incarnation, he’s deifying this woman, Beatrice, ten years deceased, who died premature, and looking at the eternal light of her smile like the first primeval men looked at Diana as the source of the perennial springs.

And he follows Beatrice up to the light into Paradise, up to the stars.

But it begs the question: is he forgiving fallen Eve, or rather reincarnating prefallen Eve—Beatrice is perfect, she died so young, she can’t talk back except on the page he’s writing,

Because where is his actual wife in all this—of course, she and her family exiled him, he’s exiled because of her, ain’t no way he’s forgiving her

Because forgiving fallen Eve means wading into the muck of the day to day with Eve, Can you do this,

And because this is not the same as foolishly brutishly spinning out in that hell-like cul-de-sac of Circe’s island that we’re talking about, it’s following Persephone to the light (although maybe it’s being nice to Circe).

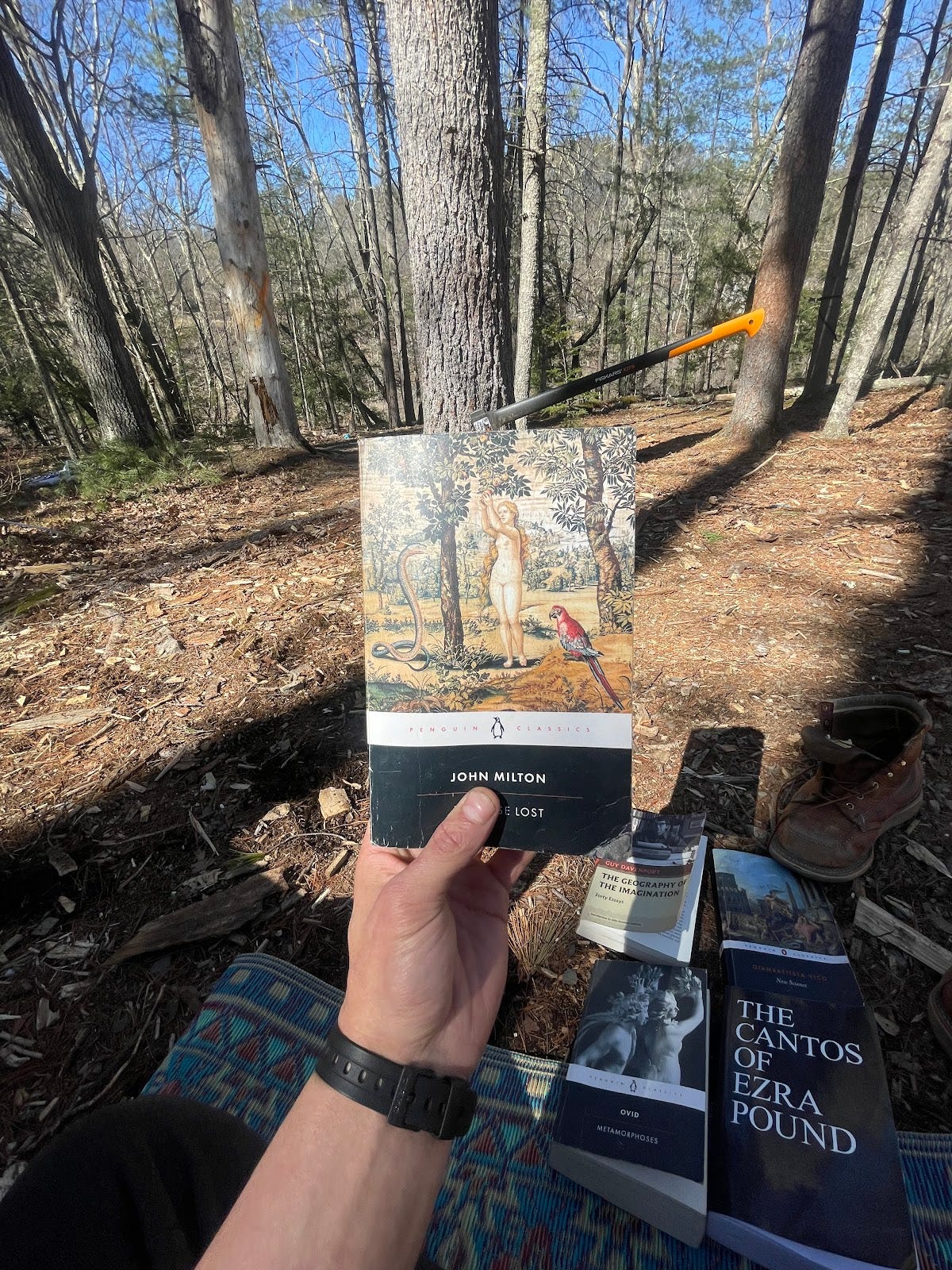

But it’s now Thursday again, and like I was saying, I just wanted to prepare myself to read the Cantos, I think I’m ready to read Pound’s Cantos now.

Vico, The New Science, 220.

Miltoni, Paradise Lost, IX, 643-645

Dante, Purgatorio (tr. Hollander), XXVII, 115-7

insanely high level work… Dante is just reincarnating prefallen Eve… wow

damn..