HOMER - OVID - VIRGIL - GENESIS - CHRIST - DANTE - VICO - PARADISE LOST - ANNA KARENINA - THE GOLDEN BOUGH - EZRA POUND - GUY DAVENPORT.

Thursday, March 6

7:31 am. Headed 90 minutes into the middle of the state to work with Eric on the house he’s renovating. Back exiled (yurted) since Monday. It’s way out there, on a small road, a house in the middle of a big snow-covered field. By a creek.

It rained all day yesterday—Ash Wednesday. I walked Lila around noon then wheeled two wheelbarrows of wood up the hill, to the yurt, and all day didn’t leave the yurt. Giving up chain smoking, overeating, and mindless phone use for Lent—deliberate phone use only!!

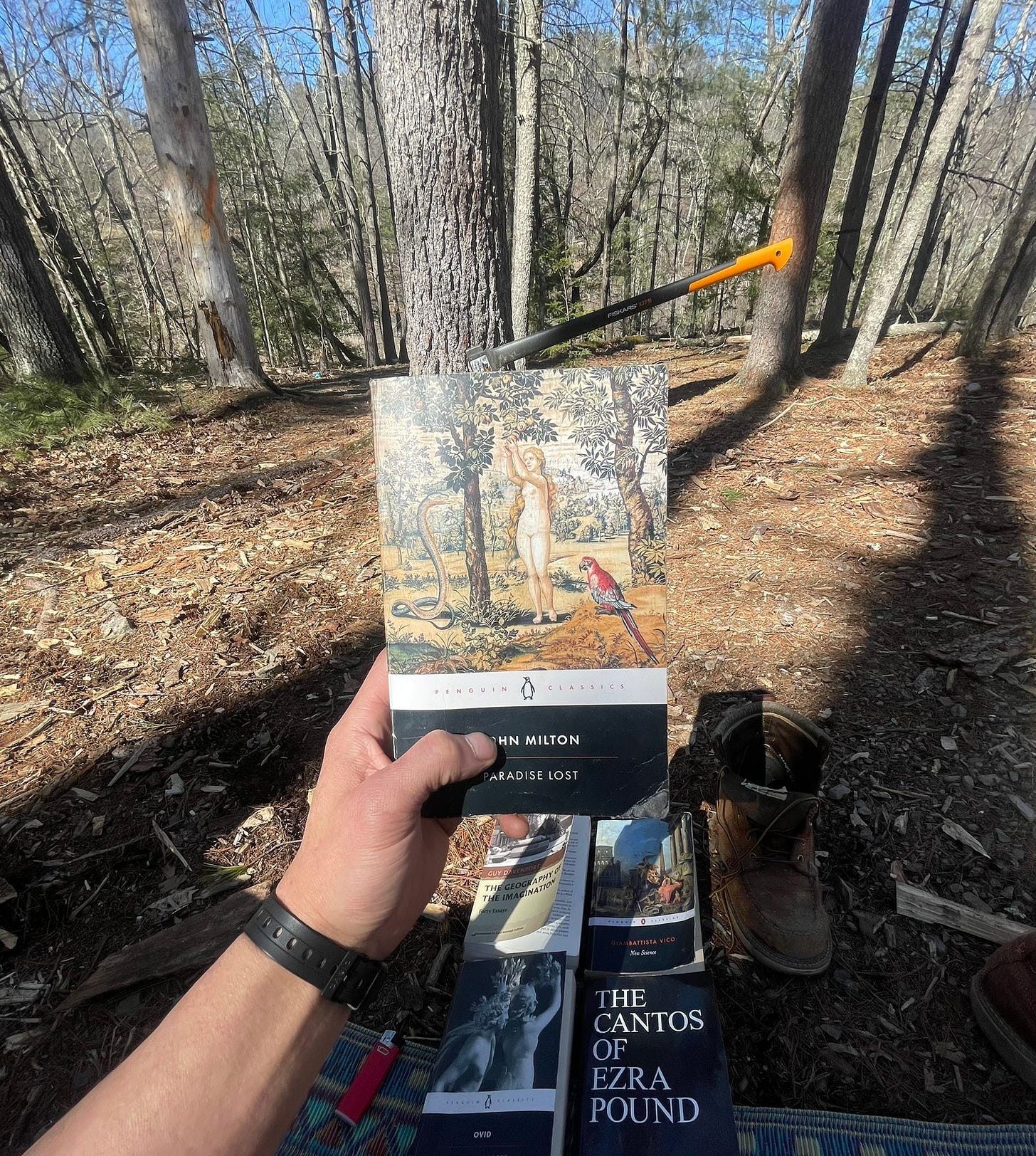

All afternoon I sat in the yurt and tended the fire, the rain pattering, reading Guy Davenport’s three essays on Ezra Pound from his collection The Geography of the Imagination. Harold gave me Pound’s Cantos last birthday, my 33rd, when I was first going hard on Dante. I’m finally understanding Pound. Preparing to really read him through. One of the essays, “Persephone’s Ezra,” is about how Pound’s Cantos are full of Circe’s, Persephone’s, Penelope’s. The Cantos, Davenport says, traces Odysseus’s path home, from Circe to Persephone to Penelope: Circe being the fixed, cthonic, seductive force, who through magic turns men to beasts, reduced to lust and gluttony, stuck in that “hell-like cul de sac” island Odysseus almost gets stuck on (Book X); whereas Persephone, whom Circe sends Odysseus to, in the underworld, as a condition for leaving her island (Book XI), is “the power of moving from dark to light, from formlessness to form, from Circe, whose inhuman mind is instructive but tangential to the life of man, to Penelope, whose virtues are domestic, an unwavering continuum:

this is the grain rite

near Enna, at Nyssa:

Circe, Persephone

so different is sea from glen that

the juniper is her holy bush.

More Davenport: “Pound was intuitively drawn to speaking of women and trees as if the one transparently showed something of the beauty of the other” (222).

Drawn to “the Odyssey, a poem about a man who thought trees were as beautiful as girls, girls as beautiful as trees; … who in the darkest trope of his wandering was sent by the witch-master of the lore of flowers and leaves, Circe, to the dwelling of Persephone, whose mystery is the power of eternal regeneration, in order that he find his way home.”1

Persephone (or Proserpine, or Kore) is the daughter of Demeter (or Ceres), the goddess of agriculture, “first to furrow the soil with the ploughshare, / first to give corn to the earth and nourishing food to mankind.”2 It is the Golden age of Saturn, there are no seasons yet, it’s eternal spring. Humans pluck fruits and flowers from the earth at will. Persephone, a young virginal maiden, is picking flowers in a field near Enna one day, when she’s transgressed upon and abducted by Pluto (or Dis, or Hades), and taken down underground to be his wife. When her mother Demeter discovers this, she causes famine upon the lands. Zeus (or Jove, or Jupiter), who had given his brother Pluto permission to take Persephone, when he sees the fields gone barren, agrees to let her return to earth so long as she refrain from eating anything down in Hades. Pluto gets wind of this and feeds her pomegranate seeds, ensuring her return. Zeus as punishment decrees that Persephone must spend half the year underground, as Pluto’s wife, and the other half—during spring—aboveground with her mother. And thus were the seasons created.

In another late Canto, CVI, Pound writes:

And was her daughter like that;

Black as Demeter’s gown,

Eyes, hair

Dis’bride, Queen over Phlegathon,

Girls faint as mist about her?

The strength of men is in grain.

This Davenport essay gets me revisiting Persephone in Ovid and Vico and Homer, and Persephone, I realize, is related to Eve: both are virginal maidens found alone surrounded by flowers in a garden when they’re plucked away from their pre fallen state by the king of the underworld, tempted to eat of the forbidden fruit: Eve is in her garden when approached by Satan, in the form of a snake, and tempted to eat the apple; like Persephone is tempted to eat the pomegranate seeds by Pluto. Both fall from a state of eternal spring, to a realm of difference—dark and light, good and evil, spring and fall. Pluto (Dis) is the pagan Satan.

Persephone, to Pound, is “the sign of youth radiant before its doom… the indwelling spirit of springtime, the miracle of transformation— “his guide toward the light he sought.”3

*

At 8:05 a.m. it starts raining. I wake up from a nap to us pulling into a construction store for tarps. Standing under this metal awning, typing this, it’s clattering loud on the metal how hard it’s raining. Thought spring was finally upon us, but it appears there’s some winter left yet.

This idea of Pound looking to Persephone as this divine female archetype of transformation hits for me since I’ve been trying to figure out what these archaic symbols of maiden worship have to do with the gnostic Christian notion of the divine feminine—the idea of Christ’s forgiveness of Mary Magdalene redeeming Eve’s sin for causing the Fall—which in turn have to do with the Dantean Troubadour notion of the mystical divine beloved, how Dante furthers this progression Christ starts of forgiving Eve, and by extension women, by elevating a woman to a divine status, and in so doing further redeeming Eve’s original sin. I’ve been trying to trace back the roots of Christ’s death and resurrection to earlier stories of journeys into and back from the underworld, of deaths and resurrections—like Odysseus must visit Persephone in Hades on Circe’s bidding, like Heracles and Orpheus must also descend underground and ascend as part of their trials. Persephone’s myth, of being abducted into Hell for half the year, like Christ is killed and sent underground to harrow Hell on Good Friday, and then led back to the light, like Christ resurrects, come spring and Easter Sunday, respectively, seem related.

Davenport describes Persephone as the divine female archetype for “the power to grow toward renewal, to think, to reproduce—against greed and ungrowing matter.”

Davenport speaks of the force throughout the Cantos “that reclaims lost form, lost spirit, Persephone’s transformation back to virginity.”4

The night I read the essays though, I think of them literally.

Circe is all seduction and witchcraft and dark female magic, pure cthonic gestation without growth, tangential and static and raw: her effect is literally that of a drug that keeps man stuck in lust and gluttony, reduced to unthinking beasts. Persephone represents the process by which that same fecund force transforms. While Penelope represents Circe domesticated, that raw primal generative force tamed. All these botanical maiden symbols represent early civilizing forces on savage primeval man—like how women civilize men, how stories help them imagine a new way, to curb their baser impulses for something higher.

And what about Pound’s infatuation with tree maidens. We’ve long since worshipped trees and tree kings, I consider, looking out the window at the rain, trees were here when we roamed the great forests, we razed them to create fields for growing crops, they feed the eternal fires of the early priest-kings, they furnish our houses, the proverbial or literal walls of our cities. Eve eats from the tree of good and evil, like we started using trees for our purposes, and Christ gets nailed to a tree (the tree-cross) to redeem Eve’s sin. Faulkner’s Caddy climbs a tree to look into the house—to discover the adult world of life and death, good and evil—and little girl-Quentin, Caddy’s incestuous love child, climbs down a tree to escape the tomb of the oppressive family home on Easter Sunday morning (in Faulkner’s retelling of Easter, The Sound and the Fury)—“Caddy smelled like trees…” And now here’s Davenport saying Pound worships his tree women:

The milk white girls

Unbend from the holly-trees

*

At the jobsite, a little after 9, we pound Celsius’s, take our final tokes, and get to it. Eric gets to finishing sanding upstairs, Thor to mending the missing tongue and groove flooring from the part of the floor we had to redo, whereas I get to demoing the framing between the living room and the kitchen—pry-barring and hammering off the old wood. Eric’s got the industrial stand-up sander going, and Thor is combination table-sawing and multi-tooling off the bottom lips of the replacement tongue and groove pieces to slide into their slots just right. Meaning it’s loud as shit. I throw on the noise cancelling cans over my balaclava that’s doubling as a dust mask, and crank Paradise Lost.

The strength of men is in grain.

The Fall, in one sense, and most crudely, is about the problem of the rogue, intellectually autonomous woman, with her own desires, her own designs, acting outside the control of controlling man. It’s about the pitfalls of a relationship, the challenges of marriage, or even the paths our lives take, of repeated falls, ever increasing knowledge of good and evil and betrayal and cruelty and death.

In another, broader sense, the Fall is historical, marking the shift from Eternal Spring to Seasons. This means, most literally, the shift from hunting and gathering to farming—from picking self-seeding fruits, to planting one’s own. From Ovid’s earliest “Golden Age” of Saturn, pagan Eden, when “no pine tree had yet been felled”—no forests had been razed to create fields to grow crops—and the earth was “untouched by hoe, unscathed by ploughshare,” and humans still wandered gathering what fruits they could. The fall marks the shift from this age of Saturn to the age of Jupiter (or Jove, or Zeus, or Thor, or in Egypt, “Jupiter Ammon”). Jupiter is the first God, “the first divine myth” invented by man, according to Vico,5 the god of lightning and thunder which represents the first higher force that brute humans, bowed over scavenging for nuts and fruits and berries since the universal flood, looked up to and feared and acted with reverence towards, that is, prayed to (for better weather). “[Jupiter] did not destroy the human race with his bolts... he stayed the giants from their brutish wandering.”6 “When they beheld Jupiter’s lightning bolts, terror subdued them, laying low not only their bodies but also their minds, in which they imagined the frightful idea of Jupiter… and this frightful idea inspired piety, and thus planted in them poetic morality… minds must be laid low and humbled if they are to profit fully from the knowledge of God.”7

Vico’s 1744 New Science, which Joyce drew from to write Ulysses, which Auerbach read for ten years and first translated into German, argues that the primeval myths of antiquity are not oracles of wisdom we can read today and extract fully formed knowledge from; rather, they represent attempts by early humans to make sense of very literal and real living circumstances, changing practices, new religious rites. They are the stories that what he calls the “theological poets” invented and shared that led humans to developing the first civil societies, groups living in unity, in one place, growing crops, rather than roaming endlessly like the giants on the primeval forest. Without understanding what circumstances these early humans were facing, we misapprehend Homer; we can’t overlook just how savage and crude a world these stories were created in.

And but so it was from this first instance of praying to thunder and lightning, which happened across cultures independently, that humans began practicing religion, which simply means looking to some higher force to humble oneself beneath, to restrain oneself for, with the idea that this would bring a better future. (“Religion” is from religare, meaning “to bind;” and “divine” is from divinare, meaning “to tell the future;” so something to bind oneself to, a reason to restrain oneself, with the idea of creating a better future.)

This led to the earliest sacred rites, the first of which was marriage, the idea of picking and staying with one woman rather than sleeping with anyone; and burial, the idea of burying and acknowledging the individual souls of our dead, rather than leaving them out to rot. This is why the first stories are about marriages (Adam and Eve), and burials (lists of names of family trees).

This idea of forestalling immediate impulses only became necessary for those humans who stopped wandering, who found (or razed forests to create) lands to till, who planted crops and then had to wait out the winters (this isn’t the case during Persephone’s Eternal spring, in Eve’s prelapsarian garden).

Here’s Vico on the early wanderings of the pre-agricultural humans, post-flood, and the significance of marriage as the earliest sacred rite:

Pursuing shy and intractable women, fleeing the wild animals which were so abundant in the great primeval forest, and searching for pasture and water, they were after many years so widely scattered that their condition was reduced to that of brutes. Then, … they were shaken and roused by a terrible fear of Uranus and Jupiter, the gods they had invented and embraced. Some of them now finally stopped wandering and took shelter in certain places. Here they settled down with certain women. And in their fear of the deities they perceived, they celebrated marriages, engaging secretly in religious and chaste carnal unions. In this way, they founded families by bearing certain children.8

In order to make it through winter, you must stay still in one place rather than perennially flee and wander; you must form a solid household unit, conserve resources, act according to knowledge of the future rather than immediate desires.

*

Around 1 p.m. we head into town for sandwiches for lunch. I spend the afternoon ram-boarding the upstairs rooms Eric finished sanding this morning, at one point getting hit with a strange stinging snow squall, combined with violent wind gusts that has the snow coming into the window sideways, which I’d opened to let out the dust, all while the sun was out and glinting. I listen to Book 8 or Paradise Lost, then to about two hours of The Golden Bough, parsing through these new insights, trying to connect them:

So the Fall, both Eve’s and Persephone’s and primeval man’s, marked a shift from aimless wandering, inconsequential frolicking, eternal spring, to a sudden awareness of seasons, dark and light, good and evil—an awareness of death, through exposure to Hades, to Satan… the sudden need to stay in one place, to humble oneself beneath something higher and not give into immediate impulses to make it through the literal winter to spring and the return of crops.

And the first ritual of this humbling to make it through winter was marriage.

And Paradise lost is about Adam and Eve, the first story, the first people to attempt marriage.

About the disintegration of that.

And the reason to try to curb our immediate impulses, through a thing like marriage, in the first place, is to get through the winter, back to the renewal of spring,

And but Persephone herself is the embodiment of the renewal of spring… Yet both Eve and Persephone are tempted and transgressed upon by the king of the underworld…

~

That night in the yurt, I finish Anna Karenina. I’d listened through the final, eighth part twice already, but both times fell asleep, initially finding it difficult to understand why the story beyond Anna mattered; once she died I felt like that was the end of the book. It’s also, I realize, a retelling of the Fall, about the ramifications of an Eve-like transgression—Anna gets tempted away from her marriage by Satan-Pluto-Vronksy, and the results are catastrophic. Levin remains patient and stays tending to his garden, he forgives Kitty for rejecting him and, like we await Persephone’s return each spring, awaits her return. And she returns, miraculously. Vronksy falls into a deep depression after Anna falls, then enlists to fight in the war. Levin goes all mystical at the end, and has this moment of transcendental revelation he can’t explain, and that doesn’t cohere with his recent conversion to Christianity: How could this feeling be limited to Christians only, he wonders. He decides that every religious leader, of all denominations, must have felt something like this, and that they were all drawing from the same source.

Then a storm hits and lightning strikes and it scares the shit out of Levin. He’s humbled before God. He’s so relieved to find that his wife Kitty and his son are okay, and resolves to dedicate himself to tending to and caring for them. Kitty realizes she will make the same mistakes over and over, but decides that that’s okay.

PARTS TWO AND THREE SOON…

The Geography of the Imagination, 223

Ovid, Metamorphosis

The Geography of the Imagination, 209

The Geography of the Imagination, 218

The New Science, 147

Ibid, 148

Ibid, 207

The New Science, 8-9