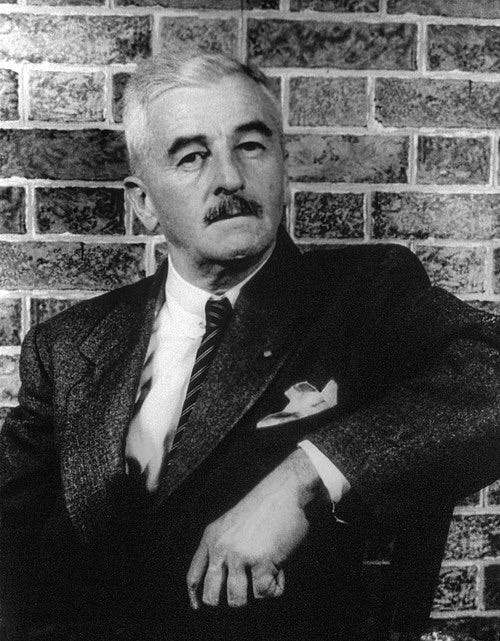

The Reason why Faulkner is Goated

Faulkner is goated

The reason why Faulkner is goated is that all the foundational questions he’s asking—what a possessive man might do about a disobedient woman (what Adam and Eve is about), how to curb the urge to control women and people, how to find one’s way to the Good amidst possessiveness, greed, vice (what all great stories are about, starting with Genesis and continuing in the Gospels)—these questions are not theoretical for Faulkner. They’re real, he feels them—and it shows that he does. His novels, then, chart the miraculous, courageous triumph of light over darkness IN HIMSELF. The reader is invited, indeed induced to feel these core shadow urges in themselves, in all their horror, and led to see them through to something different. It’s no triviality that his most formative, important story, The Sound and the Fury, is set over Easter weekend (April 6, 7 and 8, 1928), the dates of the events that redeem the Fall of man. Faulkner’s redemptions are always of women: Miss Quentin escapes the tomb of the oppressive patriarchal home on Easter Sunday morning; Lena Grove escapes at the end of A Light in August; and even Addie Bundren gets her cutting, unsettling say from beyond the grave, amidst the chorus of her needy bumbling offspring, in As I Lay Dying. And yet, the path to this point of on-paper literary humanism is not pretty: one senses Faulkner has to wrestle himself to get there, in the realest way. This very real wrestling is what is lacking in contemporary literature: One never doubts whether Ben Lerner (bless his soul) feels so possessively and wrongly towards a woman that it could be legitimately problematic. One never for one second fears that Franzen could have wrong politics. I needn’t even mention Sally Rooney‘s political pamphleteering. Adam is NOT HAPPY when Eve returns from her foray with the snake, and it’s unclear from the telling, as evidenced by the range of interpretations of the fall, whether Eve is legitimately to blame. It’s a legitimate fall and failure, with stakes, that results from this story. If you don’t read this story in this way, of how you might be complicit, you’re reading it wrong. If you don’t confront the Judas in yourself, filled with impotent rage, greed, possessive misogyny at Christ’s forgiveness of Mary Magdalene, despite her lifetime of whoring, you’re not reading the gospels right. Indeed, if you’re not confronting the heroic, seismic act Mary Magdalene achieves, of forgiving herself—allowing yourself to be forgiven, the stunning grace required to do so—you’re not reading the gospels right. In order to resurrect, you must truly descend. In order to find your way back, you must truly lose yourself in the desert. Must truly go there. Faulkner goes there. “Once a bitch, always a bitch, what I say. I says you’re lucky if her playing out of school is all that worries you. I says she ought to be down there in that kitchen right now, instead of up there in her room, gobbing paint on her face and waiting for six n——s that can’t even stand up out of a chair unless they’ve got a pan full of bread and meat to balance them, to fix breakfast for her….” starts Jason the money watcher’s monologue—the money watcher of the Compson clan, like Judas was Christ’s—set on Good Friday of Faulkner‘s 30th year. Jason continues, a bit later: “I never promise a woman anything nor let her know what I’m going to give her. That’s the only way to manage them. Always keep them guessing. If you can’t think of any other way to surprise them, given them a bust in the jaw.” And of course, Jason gets ridiculed in the end when Miss Quentin steals back all the money he’d stolen from Caddy, that Caddy had sent Jason for Quentin. But it’s only by looking into the abyss, by going fully into the darkness and finding your way back, that you can lead a reader who finds himself fully in the darkness back to the light. It’s no easy task. Virtuous posturing, self-righteous sneering, will not do. If you go there, today, you will be castigated, that is to be sure. And yet—this remains the task.

omg u snapping !

Spot on❣️